Introduction

This is a follow-up to my previous introduction to abstract groups.

Let’s recap what we’ve been doing so far. We have these things called “groups”, with an associative operation $\circ$ defined between elements, identities and inverses. Addition on real numbers is a group. Division on integers is not, since $ 1/2 \notin \mathbf{Z} $.

We then looked at maps between groups written $ f: G \rightarrow G’ $. Homomorphisms, where $f(a) \cdot f(b) = f(a) \cdot f(b)$ seemed interesting in the way they preserve some sort of structure between groups. Isomorphisms present seemingly disparate groups as one.

Let’s see if we can break these maps into more detail.

Kernels, Images and Centers

The collection of elements “reached” in $G’$ by applying $f$ to elements in $G$ is called the image of f:

The elements in $G$ that get mapped to the identity in $G’$ are the kernel of $f$. I like to think of these as items in $G$ that get “smashed” down to $e’$:

Finally, the center of a group are those elements that commute with other elements in the group.

Normal Subgroups

In our previous post we saw that a subgroup $K \subset G$ is just a subset of $G$ with group properties. What’s more interesting is a normal subgroup, where for any $k \in K$, $g k g^{-1} \in K$ as well, for $g \in G$.

Note that what’s special here is that $g$ is in $G$, not necessarily $K$. In other words, you can surround an element in $K$ by an element in $G$ and its inverse, and stay within $K$ itself - that’s what’s cool. This property applies to kernels of a homomorphism, which we’ll see now.

Kernel of a Homomorphism

Consider the kernel of a homomorphism $ \phi: G \rightarrow G’ $, which we write as $ \ker(\phi) = \{ g \in G : \phi(g) = e’ \} $. It turns out that kernels are subgroups of $G$, but a homomorphic kernel is also a normal subgroup. The proof is straighforward.

Consider $b \in ker(\phi)$ and $a \in G$. We want to show that $ker(\phi) \subset G$ is closed as a normal subgroup. In other words, that $a b a^{-1} \in ker(\phi)$…in other words, that $\phi(a b a^{-1}) = e’$. We use the homomorphism property:

$$ \begin{align} \phi(a b a^{-1}) &= \phi(a) \cdot \phi(b) \cdot \phi(a^{-1}) \ & = \phi(a) \cdot e’ \cdot \phi(a^{-1}) \ & = \phi(a a^{-1}) \ & = \phi(e) = e' \end{align} $$

So indeed $a b a^{-1} \in ker(\phi)$. This is a useful point to remember: the kernel of a homomorphism is a normal subgroup. We’ll see later that the converse is true: every normal subgroup can be seen as the kernel of some homomorphism!

Equivalence & Mod Math

Let’s recall some simple modular arithmetic. Say we are operating in modulo 5. Then $$0 = 0 \pmod 5, 1 = 1 \pmod 5…4 = 4 \pmod5, 5 = 0 \pmod 5, 6 = 1 \pmod 5…$$ We can then do additions such as $9 + 5 = 14 = 4 \pmod 5$. Notice the cyclicality - that should send some sparks flying in your brain (think cyclic groups)!

This leads to the notion of equivalence classes, which is just a generalisation of equality. For any two elements $a, b$ (in some set), we say $a \sim b$ ("$a$ relates to $b$"). A relation $\sim$ has the following properties:

- $a \sim a$ for any $a$ (reflexivity)

- $a \sim b$ implies $b \sim a$ (symmetry)

- $a \sim b$ and $b \sim c$ implies $a \sim c$ (transitivity)

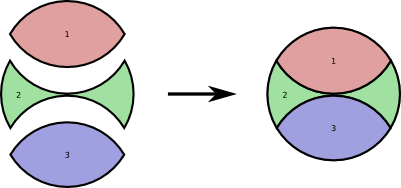

These are properties we’d like for a notion of equality. In our modular example, we could say $3 \sim 8$ since $3 = 8 \pmod 5$. In this specific context, we sometimes say “$a$ is congruent to $b$ mod 5” and write $a \cong b \pmod 5$. Equivalence relations induce a partition on a set: disjoint subsets that together form the whole set:

In the case of integers $\pmod n$, each partition corresponds to a set of integers, formed by given integer $a < n$, with all integer multiples of $n$. So we have a class

$$ \bar{a} = { …a-3n, a-2n, a-n, a, a + n, a + 2n, a + 3n… }. $$

We then have a new set of order $n$ of these equivalence classes, that we call $\mathbf{Z}/n\mathbf{Z}$. Namely,

$$ \mathbf{Z}/n\mathbf{Z} = { \bar{0}, \bar{1}, … , \overline{n-1} } $$

Cosets

Fantastic, so now we’ve seen modular arithmetic as a partition of the integers, into equivalence classes. Let’s generalise this notion, through the use of cosets.

Quick reminder: we’re doing group theory here, where we have an arbitrary operation $\circ$. We use the symbols $+$ and $*$ because they’re familiar. But never forget, we want to generalise to any group operation $\circ$, and will interchange notation. Try to keep reminding yourself of this whenever you see these symbols.

Cosets are easy. Take a subgroup $H \subset G$. Take a fixed element $a \in G$. We now have a coset of $H$ in $G$, denoted $aH = \{ ah : h \in H \}$. Voilà! A subtle point is that group operations are not always commutative, so technically this is a left coset; you can imagine what a right coset is.

Here’s what’s really cool: if you think about it, the left (or right) cosets of a subgroup partition the group. We’ve already seen this with modular arithmetic. The subgroup there was $n\mathbf{Z} = \{ …-3n, -2n, -n, 0, n, 2n, 3n… \}$. The group was $\mathbf{Z}$. We partitioned $\mathbf{Z}$ (the group) into $\mathbf{Z}/n\mathbf{Z} = \{ \bar{0}, \bar{1}, … , \overline{n-1} \}$.

The coset view of this partition is as follows: for each element $a \in \mathbf{Z}$, the equivalence class $\bar{a}$ is given by $a \circ n\mathbf{Z}$. The $\circ$ operation we’ve been using is $+$, but as we’ll see now, we should not get too attached to this.

Quotient Groups

Alright, I promised an introductory generalisation of modular math, and here it is. The concept is deep and we’ll explore it further. The “thing” $\mathbf{Z}/n\mathbf{Z}$ is called a quotient group, more generally $G / H$ for a group $G$ with subgroup $H$. However, it turns out we can’t choose just any subgroup $H$; it actually has to be normal.

Why is this the case? Because we’ve partitioned $G$ into a set of equivalence classes, but for it to be called a (quotient) group, we need a to define a group operation. For this operation to be naturally well-defined, we’ll need normality. As the French would say, that allows “transport de structure” from the operation already defined on $G$.

In the modular case we had new equivalence classes denoted by cosets $a + n\mathbf{Z}$. We’ll now have equivalence classes denoted $a \circ H = \{ ah : h \in H \}$. I hope that whets your appetite regarding the power of quotient groups.

Conclusion

Quotient groups, a generalisation of modular arithmetic, require a fair bit of build-up to understand their true beauty. I hope I’ve presented an introduction that highlights some of the intuition behind them. In our next post, we’ll define quotient groups properly, and explore them in meaningful ways. Until next time!

Ackowledgements

A huge thanks to anyone contributing to open-source in general, ’tis the best way forward. In this specific case, thanks to Harvard’s online Abstract Algebra course.

All rights reserved