Introduction

The term “Bitcoin” is becoming more and more widespread. However the core technical details of the cryptocurrency are often brushed aside, or lumped together. Bitcoin is in fact a decentralised payment system, characterised by multiple features. In this post, I hope to identify and briefly explain these key features.

Once we’ve identified the overall architecture of the system, I’ll try and use it to develop some views on where things are headed.

Overview

In its essence, Bitcoin is just a public ledger network. Computers come together to form a network, and each computer stores the ledger. A simplified ledger could just be a table of identities and account balances:

To transact, Alice and Bob can pass a message to other nodes in the network saying that Alice paid Bob 5 Bitcoins (BTC). All nodes on the network then update their ledgers:

This differs from traditional transactions within or between banks, in that the ledger is completely decentralised. This also means there is no single entity that can be held accountable for what goes on with the ledger. Furthermore, the ledger is completely public.

The Bitcoin system incorporates cryptographic techniques to deal with the issues that arise from such a network, namely:

- Authenticity of transactions and balances

- Privacy

- Sequentiality in time: which transaction came first?

Let’s explore these techniques.

Transaction Authenticity

Earlier, we mentionned that Alice could pay Bob 5 BTC by announing it on the network, thereby signalling all nodes to update their ledger. To prevent anyone from pretending to be Alice, this is done cryptographically.

The announcement is the “message”. Alice posseses a personal, secret “private key”, which she uses alongside the message to create a “signature”. In other words, signature = f(private key, message).

But how do other nodes use this to determine authenticity? It turns out that Alice can also have a “public key” (which of course everybody knows). Nodes can verify the broadcast message through a seperate function v(signature, message, public key) that will essentially return true or false. If false, it would mean the correct private key was not used to generate the signature, and the message is thereby invalid. Note that a good consequence of this is that the message can’t be maliciously or otherwise altered as it passes accross the network: that would invalidate it. The mathematics used is rooted in elliptic curve cryptography.

Since everybody has a public key, we use that as recipient address as well. In other words, when Alice is sending money to Bob, she actually sends it to his public key. This is simply reuse: no cryptography is being done here.

The Actual Ledger

Now that we’re getting the hang of transactions, let’s remove the oversimplification from the ledger. In reality, account balances are not stored at all. How then can we be sure Alice has sufficient funds to send Bob 5 BTC? When she seeks to spend the 5 BTC, she must reference previous transactions where she received bitcoins, for a total of 5 BTC.

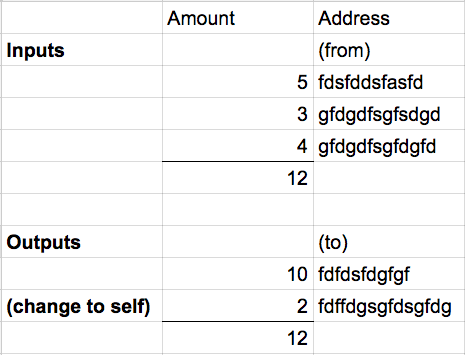

In other words, a transaction message is comprised of inputs and outputs. All inputs must be fully spent, so if Alice wished to send 10 BTC to Bob, using inputs amounting to 12 BTC, she would send herself 2 BTC in the outputs, as change:

Hence ownership of Bitcoin is passed along in a chain, where the validity of each transaction depends on that of previous transactions. What does this mean? It means before transacting in Bitcoin, one has to download the history of all transactions that ever took place, and sequentially verify them through signatures as discussed earlier (at least, that’s the most secure thing to do). This is the cost of a decentralised network. It usually takes about a day, and only has to be done in aggregate once: it can then be done incrementally, which takes much, much less time.

In addition to validating each transaction through signatures, transactions are checked for double-spending: the same input cannot be used in two separate transactions.

In summary, the ledger is a giant list of transactions. Possessing Bitcoin means having transactions where your public key is an output address, and where those transactions haven’t been used as inputs for another transaction yet.

Anonymity

The Tor network can be used to prevent your public key/address from being associated to a given computer or IP address.

In addition, an individual can create a new public key for each transaction, since there are so many possibilities, to avoid transactions being associated to the same address. Note however that inputs and outputs used within a given transaction are visibly associated, and there are statistical attacks to link addresses this way.

An important point is that if a given public key is associated to Alice, she essentially loses anonymity forever, for those who know the association. For instance, if Bob found out Alice owns address A, creating a new address B and sending her money from A to B would not solve the problem, since that transaction would be public, and Bob could trace it. Maintaining anonymity through the careful use of addresses is thus very important.

Double Spending and Sequentiality

Given that messages are passed along the network, nodes may receive them at different points in time.

This creates a vulnerability for double-spending, since you can’t trust a simple timestamp on a transaction: the creator could write anything. For instance, Alice may send Bob 5 BTC by referencing some input #E74, prompting Bob to send her some product. She could then reference the same input #E74 to send money to herself. Nothing stops her from doing this: she just creates the message using custom software, and signs it with her private key.

Some nodes, like Charlie, on the network may receive Alice’s self-payment transaction first, and thereafter count the real transaction as invalid. Bob will have sent his product, but wouldn’t be able to use that money to buy things from Charlie and others. There would be different versions of history on the network. Bitcoin uses a key innovation to overcome this, called the Blockchain.

The Blockchain

The Blockchain allows for a universal agreement on transaction order accross a decentralised network. It groups transactions into blocks, with each block containing a reference to the previous block:

Transactions in the same block are considered simultaneous. Consider an existing chain of blocks. How do we decide which block comes next? Any node in the network can group transactions into a new block and present it as a candidate. The first candidate to be unlocked becomes the next in the chain.

The way a block is unlocked is that it is run through a hash, in Bitcoin’s case SHA256. The output of the hash is a string. It is nearly impossible to predict this output. Consider the following example: the input varies only in one letter, but the output varies completely.

The input “meow” generates

404cdd7bc109c432f8cc2443b45bcfe95980f5107215c645236e577929ac3e52

Meanwhile, “moow” generates

cc7856417792e2efcd6dc170183ae9c91bb73cddc77d8e1e40c7f9c519f041d7

Equivalently, it is hard to tell which will be lexicographically bigger. The way the Blockchain uses such hashing is as follows: nodes must hash the candidate block as well as a random number, until the hash is smaller than some target value.

It would take a single machine on the order of years to solve a block, so we are essentially relying on one node getting “lucky”. When a block is solved, that node broadcasts the correct guess, and the block is accepted as the next in the Blockchain. It is extremely unlikely for multiple nodes to solve the same block at the same time. In the event of a tie, multiple candidate paths are considered, until one path becomes longer. Thus the longest chain is considered the true one. At present, one generally waits for a block to be about six blocks into the chain’s tail, just to be sure. The probability of being in the wrong tail (one that will lose a tie) decreases exponentially in the number of blocks into the Blockchain.

The fundamental beauty of the Blockchain is that it makes it extremely unlikely for a given party to “fake” a version of history (and thus double-spend), as long as the majority of computational resources in the network are not owned by that party. It does this by bringing random guessing into the picture.

Solving Blocks

Nodes are rewarded for trying to solve blocks by earning Bitcoin for doing so successfully. This is how new coins are injected into the economy. Since it is so unlikely to guess a block correctly, people tend to form very large cooperatives that split the proceeds when a block is solved. The number of coins created drops gradually, until no more will be added around 2140. After this, senders will pay a small transaction fee to incentivise it being processed in a block.

Conclusion

We have seen that Bitcoin offers an electronic payment system that is fully decentralised. Authenticity is maintained through cryptographic signing. Privacy can be maintained by randomly generating public addresses. Finally, and probably most importantly, a single decentralised version of history is maintained through the innovation of the Blockchain.

Now that we understand the basics of Bitcoin, I’ll try and formulate my current opinion on where things might be headed

Acknowledgements

My understanding of Bitcoin was initally heavily influenced by this video and the original paper, which will be reflected in my exposition.